(Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, Santa Monica) It started with a hairball. Margie Livingston wondered if she could draw the light filtering through that hairball —and with this challenge, launched herself into an exploration of depicting 3D space in 2D space, but always by using a model. In order to produce one of her early paintings, Livingston would build a model, often a grid-like structure of string and wood. Then the small object standing in her studio would provide inspiration for an atmospheric, tasteful oil study in space, form and light.

(Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, Santa Monica) It started with a hairball. Margie Livingston wondered if she could draw the light filtering through that hairball —and with this challenge, launched herself into an exploration of depicting 3D space in 2D space, but always by using a model. In order to produce one of her early paintings, Livingston would build a model, often a grid-like structure of string and wood. Then the small object standing in her studio would provide inspiration for an atmospheric, tasteful oil study in space, form and light.

But recently those objects, built as models and collectively saved over the years, began to garner more interest than, or as much interest as Livingston’s paintings. And it’s no surprise that after ten years of unedited and uninhibited model-making that Livingston has developed a knack for building objects. This first show of sculptures at Luis De Jesus offers a broad view of Livingston’s newly-acknowledged talent.

Livingston is only halfway out of the closet about being sculptor; she is a painter who has begun making objects—with paint. There can be a chasm between the making and the experiencing of an artwork, but luckily that is not always to the detriment of the work. As we all make arbitrary rules to make a comprehensible reality for ourselves inside of infinity, it is quite common for an artist to set parameters for how her work will be constructed. In this case, Livingston works with acrylic paint and sees what it can do off the canvas. In doing so, that she reports that she can feel herself working through many art history giants, including Carl Andre, Charles Ray, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Linda Benglis, and even Barnett Newman. While Livingston is bridging the world of painting to the world of sculpture, she still perceives herself as a painter and describes her sculptures as “paint objects.â€

Livingston is only halfway out of the closet about being sculptor; she is a painter who has begun making objects—with paint. There can be a chasm between the making and the experiencing of an artwork, but luckily that is not always to the detriment of the work. As we all make arbitrary rules to make a comprehensible reality for ourselves inside of infinity, it is quite common for an artist to set parameters for how her work will be constructed. In this case, Livingston works with acrylic paint and sees what it can do off the canvas. In doing so, that she reports that she can feel herself working through many art history giants, including Carl Andre, Charles Ray, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Linda Benglis, and even Barnett Newman. While Livingston is bridging the world of painting to the world of sculpture, she still perceives herself as a painter and describes her sculptures as “paint objects.â€

Granted, much painting does go into the making of her objects, from cubes, dots, decals, and wafer boards; and apart from the wire stringing a length of tiny paint dots from the ceiling to floor, every object is constructed purely of paint. In what she calls “studies for spiral blocks†Livingston literally pours gallons of paint out in sheets and lets them dry for days like so much acrylic fruit leather. Each layer is made of about two gallons of acrylic paint, poured, splashed, dripped, and painted in an expressionistic manner. After making a number of these sheets she rolls the sheets into tight logs like one might roll a jelly or sushi roll. These dense paint logs are then milled with a bandsaw into two 2×4’s that are each eight feet long. Some are cut further into sections. Because of the many thin circular layers of color that are revealed, the resulting cubes look startlingly like something between a tree trunk slice and a mille fiori glass bead.

Granted, much painting does go into the making of her objects, from cubes, dots, decals, and wafer boards; and apart from the wire stringing a length of tiny paint dots from the ceiling to floor, every object is constructed purely of paint. In what she calls “studies for spiral blocks†Livingston literally pours gallons of paint out in sheets and lets them dry for days like so much acrylic fruit leather. Each layer is made of about two gallons of acrylic paint, poured, splashed, dripped, and painted in an expressionistic manner. After making a number of these sheets she rolls the sheets into tight logs like one might roll a jelly or sushi roll. These dense paint logs are then milled with a bandsaw into two 2×4’s that are each eight feet long. Some are cut further into sections. Because of the many thin circular layers of color that are revealed, the resulting cubes look startlingly like something between a tree trunk slice and a mille fiori glass bead.

Even more fascinating is how Livingston recontextualizes, subsumes, and feminizes traditionally macho art traditions, particularly those in abstract expressionism and minimalism (in this sense, she reminds me of LA artist Liz Larner). The image of Livingston heaving paint onto the floor inevitably brings to mind Jackson Pollock wrestling with his penis/paintbrush, a difference here is that after producing nearly a dozen of these canvas-free paintings, Livingston literally obliterates each one by rolling it up (with the help of a few friends) and then slices the log into lengths. The gesture of individual expression is sliced by machinery; layers of accident, collaboration, and culinary skills draw attention away from the hand of the artist and towards the process itself while at the same time, the object is clearly a finished product with presence.

Even more fascinating is how Livingston recontextualizes, subsumes, and feminizes traditionally macho art traditions, particularly those in abstract expressionism and minimalism (in this sense, she reminds me of LA artist Liz Larner). The image of Livingston heaving paint onto the floor inevitably brings to mind Jackson Pollock wrestling with his penis/paintbrush, a difference here is that after producing nearly a dozen of these canvas-free paintings, Livingston literally obliterates each one by rolling it up (with the help of a few friends) and then slices the log into lengths. The gesture of individual expression is sliced by machinery; layers of accident, collaboration, and culinary skills draw attention away from the hand of the artist and towards the process itself while at the same time, the object is clearly a finished product with presence.

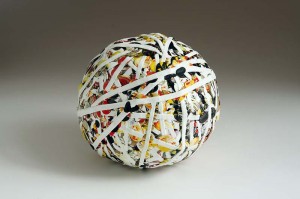

Using a similar technique of wrapping many layers of poured acrylic “threads,†Livingston also produces solid rock-like objects that she calls wraps. These look like plasticized balls of string, but when cut open, they reveal color surprises like geodes. It makes one wonder what cross sections of Jay Defeo’s The Rose (1965) would have revealed. Defeo’s obsession with layering illustrated in the sheer bulk of that piece (3,000 pounds), takes on a completely different light when you think about it in terms of cross-sections. As process-oriented works, Livingston’s works are not monumental in a good way; building up, even obsessively, sometimes productively leads to cutting and revealing.

My favorites though are Livingston’s folded paintings. Lengths of dried paint skin are neatly folded and left sitting in piles. The simple domestic act of folding these swaths of marbled color allows the object to flux elegantly between finished product and waiting-to-be-used resource. Her newest work, such as the melted wafer board, begins to reach the limits of what the plastic paint will do physically (it stretches when hung on the wall) and it will be interesting to see if Livingston’s purist rules change and if her paint will return to canvas or other support structures.

My favorites though are Livingston’s folded paintings. Lengths of dried paint skin are neatly folded and left sitting in piles. The simple domestic act of folding these swaths of marbled color allows the object to flux elegantly between finished product and waiting-to-be-used resource. Her newest work, such as the melted wafer board, begins to reach the limits of what the plastic paint will do physically (it stretches when hung on the wall) and it will be interesting to see if Livingston’s purist rules change and if her paint will return to canvas or other support structures.